The Early Workhouses in Galway

By

Poverty in Galway

The poor of Galway up till the seventies of the last century lived under the filthiest conditions of overcrowding, without sanitation or doctors. Talking of the doctors of the period Latocnaye (a French émigré) writes of the doctors of Galway at the end of the eighteenth century:

"... the cost of law and I may add, of medicine is exorbitant - not only are the poor absolutely deprived of the help of the latter, but event those of moderate means cannot afford it. The middle classes can hardly expect to see one of Messieurs, the disciples of Hippocrates, under a guinea or two guineas per visit. However it must be admitted that doctors often make it a duty to visit, for nothing, folk who cannot pay anything, and among these latter are some very well-educated and respectable persons."

"Before the union the population of Galway and Liberties was estimated to be 40,000 but the economic conditions of the people were miserable. The two was neglected and extravagantly dirty. Pigs wandered the streets, fish offal was everywhere and manure heaps were piled in the roadways. Smallpox was the scourge most dreaded as destructive of beauty and still more destructive of life. The death rate was high, and continued to go up until after the passing of the first Public Health Act in 1848."

Relief of the Poor

The whole question of the relief of the poor in Ireland had undergone prolonged and exhaustive examination from time to time both by Parliamentary Committees and Special Committees of Special Commissions of Inquiry. It had also been fully discussed in all its aspects and bearings in numberless pamphlets. The plan which finally found favour with the Government of Lord Melbourne was the adoption of the then new English workhouse system, established in 1834. The extension of this to Ireland was received with the utmost hostility in numerous and influential quarters, and in Galway and Mayo the powers of the law had to be invoked to enforce compliance with its provisions.

Dependence on the Potato

Of the vast population of Ireland, 8,295,061 in 1848, more than a third may be described as almost wholly dependent on potatoes for their daily existence the largest proportions being concentrated in Counties Galway and Mayo. They consisted of three distinct classes:

- occupiers of cabins with small farms varying in extend from one to five acres:

- cottiers living on the lands of the farmers for whom they worked, in cabins to which were attached small plots of ground of from a rood to a half or an entire acre;

- and at the bottom of the scale the labourers who had no fixed employment and no land, but who simply rented the hovels they lived in and depended for support on the patches of conacre potato ground they were able to hire each year from some neighbouring farmer.

Poor Law as an Incentive to Eviction

"It is not surprising that Ireland, left for three centuries without any provision for its poor, should have presented occasionally a mass of human misery unparalleled in any country in Europe". The desire of the landlords to clear their estates was encouraged by the disfranchisement of the forty shillings freeholders. According to the Devon Commission "the act of 1829 destroyed the political value of the forty shillings freeholder, and to relieve his property from the burden which circumstances had brought upon it the landlord in too many cases adopted what has been called the clearance system". The effect of the poor law as an incentive to eviction was the aim intended by its authors to aid the process, and in fact the number of evictions increased greatly after its enactment. After public opinion being much divided in respect to the propriety of extending poor laws to Ireland at all, the Poor Law Act, 1838, came into operation in 1839, but the workhouses were not open for the admission of paupers until 1840.

Main Provisions of the Poor Law Act

The main provisions of the act were: -

- The division of the country into unions composed of electoral divisions, which in turn were made up of "townlands".

- The formation of a board of guardians for each union - the board consisting of elected and ex-officio guardians.

- The establishment of a central authority - the Poor Law Commissioners for England and Wales.

- A compulsory rate for the relief of the poor.

- The relief to be at the discretion of the guardians, and accordingly no poor person, however, destitute, to be held to have a statutory right to relief. A preference to be given to the aged, the infirm, the defective, and the children; after these had been provided for, the guardians to be at liberty to relieve such other persons as they might deem to be destitute, priority to be given to those resident in the union, in the event of the accommodation in the workhouse being insufficient for all.

- The relief to the limited to relief in the workhouse.

- The relief to be subject to the 'direction and control' of the Poor Law Commissioners, who, however, were prohibited from interfering in individual cases for the purpose of ordering relief. The Commissioners to make orders for the guidance and control of guardians, wardens, officers, the auditing of accounts, and for carrying the act into execution in all respects as they might think proper.

Gregory Clause

The process of eviction did not seem to have been advancing rapidly enough to satisfy Government, as a few years later another provision was devised calculated to facilitate it further. This was the famous Gregory clause, introduced by Sir William Gregory of Coole Park, Gort, and Member of Parliament for the city of Dublin.Gregory in 1847 defended Lord George Bentick's scheme for giving employment in Ireland by Government lending money for the institution of railways, and commented strongly on the policy of leaving the people in such an unprecedented calamity as to be fed by private enterprise, considering that throughout a large proportion of Ireland there was no one of capital and experience equal to such an undertaking. He added that there was not a ton of Indian meal to be purchased in Galway, though there were a thousand tons in Government stores at that place, and that the people could by Government agency alone be fed in many parts of Ireland. He spoke also in March on the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1847 to Powlett Scropes's proposal to organise a general and continual system of outdoor relief for the able-bodied; and he introduced and carried two clauses into the Bill, commented on by Oliver Burke in the Dublin University Magazine of August, 1876 as follows:-

"The dreadful potato disease of 1846 engaged much of Mr. Gregory's attention. Ireland, at that period, was chiefly peopled by a peasantry in the wretched condition of squatters, whose miserable holdings were quite inadequate to afford more than a precarious support to their occupiers. Comforts were out of the question, because a worse than French morcellement had split up farms into mere squatter holdings. The low standard of life thus caused amongst the agricultural classes, and the facility of obtaining that low standard so long as the potatoes lasted, had encouraged the pernicious subdivision of the land and stimulated such an increase of population as has never elsewhere been witnessed in a country with a moist climate, and where the population is utterly dependent from the absence of manufactures, on the produce of the soil. Here, then, were two difficulties for the statesman, the one how to manage matters so that none but the destitute should receive relief, and the other how to provide an outlet for the redundant population.

"Mr. Gregory was amongst those who devoted their thoughts to those twofold difficulties. As to the latter, he proposed to the House that any tenant rated at a net value not exceeding £5 should be assisted to emigrate by the Guardians of the Union, the landlord to forego any claim for rent and to provide such fair and reasonable sum as might be necessary for the emigration of such occupier, the guardians being empowered to pay for the emigration of his family any sum not exceeding half what the landlord should give, the same to be levied off the rates.

"This clause was agreed to without opposition. Of the humanity which dictated it there can be no second opinion; it was surely humane to try and provide an outlet for the famishing people. At home there was want, at home there was a vast population depending for food upon a soil which seemed to be excepted from the primeval blessing that 'the earth should bring forth herbs and fruits according to its kind'. Fever was at home, and, worse than all, despair as to the future. But a few days sail away, across the Atlantic there lay a land with millions of unoccupied acres, teeming with natural riches. Why not open a career in that New World for those who were willing to go there, and thereby diminish the pressure on the resources at home. Surely such an effort would be humane, and that effort was made by Mr. Gregory. But there remained that other difficulty of which we have spoken, namely, the absorption by undeserving persons of a large portion of the public funds. How was this evil to be met? If it were not arrested, and that, too, speedily, the tax for the relief of the poor, already a frightful burden on the land, would become intolerable. The poor rate was already so heavy that in many cases it exceeded the amount of the yearly rent of the land... Mr. Gregory proposed that a test be applied to insure that no undeserving person should get relief, and his test was that the possessor of more than a quarter of an acre of land should not be entitled to assistance. This suggestion became law, and has since been known as the 'Gregory Clause'.

"It is very easy to prophesy after the event, but on the night when the 'Gregory Clause' passed the Committee of the House of Commons, there were present in the House 125 members, many of them Irish members, and of these 125 only 9 voted against the measure. Mr. Morgan John O'Connell spoke strongly in its favour. The evil results we have alluded to were not then foreseen, certainly they were not believed in by Mr. Gregory, whose advocacy of the emigration clause is the best proof of his good motives to those who do not know the humanity and the kindness when, then and always, have marked his dealings with the tenants on his own estates".

The Archbishop of Tuam, Dr. McHale, never forgave Gregory on account of his clause, and always referred to him as "Quarter Acre Gregory". The author of The History of the Famine, Father O'Rourke stated, "A more complete engine for the slaughter and degradation of a people was never designed. The previous clause offered facilities for emigrating to those who would give up their land; the quarter-acre clause compelled them to give it up or die of hunger." John Mitchell described the clause as "the cheapest and most efficient of the ejectment acts". So great had the evil become that by an act of 1848 special provision was made for granting relief to families evicted from their dwellings.

Role of Landlords in the Relief of Poor

There were many resident landlords who did everything in their power to alleviate the sufferings of their tenants. Some of them like the Blakes, Burkes and Martins, ruined themselves financially in their efforts to avert further tragedy. "Ladies kept their servants busy and their kitchens smoking with continued preparation of food for the starving poor".

Other resident landlords, however, decided that the simplest way of dealing with the problem was to ship their surplus tenants to the United States and Canada. Bargains were made with shipping agents, and half-dying and often fever-stricken emigrants were packed into the holds of rotten ships and sent overseas. "Crowded and filthy, carrying double the legal number of passengers, and having no doctor on board, the holds were like the Black Hole of Calcutta, and deaths in myriads". It was cheaper to ship tenants overseas than feed them out of the county rates. With the wholesale evictions and the seizure of crops agrarian outrages again broke out. A Coercion Act was passed aiming at securing any arms which might have survived previous disarming acts, and under a penalty of two years' imprisonment with hard labour it compelled all persons between the ages of sixteen and sixty to give all assistance when called upon, to the police and military.

To return to Sir William Gregory, his father, who was proprietor of the Coole estate and two outlying properties, Clooniffe in the barony of Moycullen and Kiltiernan in the barony of Dunkellin, died in April 1847, one of the victims of duty during that terrible time when fever followed famine. Among the other landowners that perished through their helping the sick were Lord Dunsandle and Thomas Martin owner of the great Ballinahinch Estate.

Mortality in the Workhouses

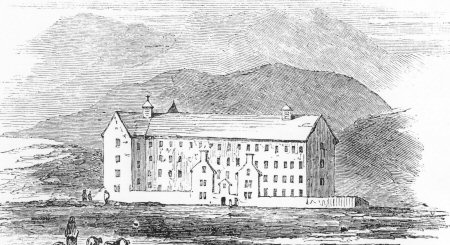

By 1st May 1848, workhouses had been established in Ballinasloe, Clifden, Galway, Gort, Loughrea and Tuam.

By the end of September of that year there were 7,480 paupers in the six workhouses and during the year 14,522 had been relieved in the institution and 11,156 had died. The mortality in the workhouses in April 1847, had reached the weekly rate of 25 per 1,000 inmates; that of the fever patients being nearly four times as high. While the maximum numbers at any one time had been 11,156 on the 27th February, 1847, from which period to the 10th April the number had gradually declined to 7,480 while the rate of mortality had continued to increase notwithstanding that reduction.

There was a gradual decline in the rate of mortality in the workhouses through the months of May and June and by the beginning of June it had descended to half the rate. It was observable, however, that during the same period the total numbers in the institutions of Galway had undergone no material decrease, the fluctuations indicate the fearful state of the pressure on the workhouses in the Spring of 1847.

The temporary fever hospitals established under the Temporary Relief and Fever Acts in the six towns only provided for 630 although 2,440 had to be treated. The total cost of maintenance of the institutions in 1847 amounted to £26,196 15s. 0d.

A photograph of the entrance to St. Brigid's, Ballinasloe. St. Brigid's is a former workhouse; this photograph is part of the Cardall collection at Galway library.

British Association for the Relief of Extreme Distress

In January 1847, was founded the British Association for the Relief of Extreme Distress in Ireland and the Highlands and Islands of Scotland which collected and distributed funds amounting to £263,251, shortly after increased by £171,533. One sixth of the total sums collected was allotted to Scotland and five-sixths to Ireland. Arrangements were entered into by the Poor Law Commissioners of Ireland with the British Relief Association for making the balance of their funds available in aid of those Unions in Ireland in which the greatest distress might from previous experience, be expected to prevail, combined with the smallest means of raising sufficient local funds for its relief.

Three of the six Unions in County Galway, Clifden, Galway and Tuam, were in the first instance, among nineteen others in Ireland, selected as likely to need assistance from the Association. To each of those Unions a Temporary Inspector was appointed to assist in the distribution of these funds, and to take care that due exertion in the collection of rates and otherwise should not cease to be made by the local authorities, in consequence of the external supply which might be given or might be expected to be given, in aid of the necessities of the district. The names of the Inspectors placed in charge of the Unions were: Clifden, John Deane; Galway, Captain Hellard, R.N., died of fever and afterwards Major McKie; and Tuam, Captain Labalmondiere.

In the other three Unions of Galway, Ballinasloe, Gort and Loughrea the means of delivering the destitute poor were limited exclusively to the funds provided by the collection of poor rates. During the famine years, especially 1847, the younger inmates of the County Galway hospitals and workhouses were attacked in considerable numbers by a peculiar and fatal nervous disease, which was fully described by Dr. Darby and Dr. Mayne; "It was characterised by the most extreme stiffness of all the muscles, similar to what occurs in lockjaw, and by such increased sensitiveness of the skin that the slightest touch or draught of air produced intense agony. It was induced by the preceding scarcity of food, and was not communicable from one person to another".

In the year 1847, the blight in the potatoes took place earlier and was of a much more sweeping and decisive kind. A very small breadth of land had been planted with potatoes in County Galway causing the great price to which they rose in the market so early in the months of October and November. The price was even then so high as to place the purchase of this food out of the reach of the peasantry, even when employed and in receipt of agricultural wages, and such fortunate labourers were few comparatively in County Galway. Few of them had ventured to plant this crop, rendered so uncertain by two years' blight, to a sufficient extent for the sustenance of their families. On the other hand, the large importation of Indian meal into the county had so far reduced the price of that and other description of meals that the money cost of human subsistence was not much greater than in seasons when the potato was in greatest abundance. In Galway, from want of enterprise or capital on the part of the landlords, employment was not available, the peasantry, being without the usual resource of potatoes, necessarily fell into severe privation; and after the exhaustion of the few vegetables they had planted instead of their accustomed food, inevitably required relief to preserve them from starvation.

Power to Dissolve a Board of Guardians

The power of dissolving a Board of Guardians, and immediately appointing paid officers for the discharge of their duties, was given by Government, apparently under some feeling of distrust as to the general efficacy of the existing machinery for the administration of outdoor relief under the circumstances existing.

It was felt that a small number of paid officers was calculated to remedy the leading defects incidental to the administration of relief by a Board of Guardians. They would not be led by any undue considerations to decline the making of sufficient rates, or the enforcement of their impartial and prompt collection.

They would have time at their disposal amply sufficient for the conduct of the general business of the Union and the control of the subordinate officers, for superintending the details of workhouse management, etc. They would be enable to devote to the various duties, instead of a part of one day weekly, many hours of every day in each week, unimpeded by the lengthened discussions unavoidable in a more numerous assemblage of Guardians.

Serious default in the discharge of the duties of the Guardians resulted in the dissolution of the Boards of Guardians at Clifden, Galway, Gort, Loughrea and Tuam, and the appointment of paid officers to act in the carrying out of their duties. The Poor Law Commissioners recorded in the case of Ballinasloe their satisfaction in which the administration of relief continued to be conducted efficiently for the most part by the ordinary means of management, viz., by the elective Board of Guardians.

Workfare

A measure of affording relief in connection with work was that each able-bodied man received rations in proportion to the number dependent on him for sustenance; and that each, however small the allowance of rations was required to give eight hours (subsequently increased to ten) at least of his time in labour at the stone depot for every day for which he received such relief.

Accordingly

"the Commissioners recommend the Guardians to establish a system of breaking stones by Measure, as the most suitable employment for able-bodied males requiring relief. The advantages of stone breaking are, that it is easy to superintend and regulate as task-work-that the materials are generally available, the implements of labour few and simple and above all, that it is less eligible to the labourer than most other employments, provided that it be vigilantly superintended and that a full day's labour be rigorously exacted from each recipient of relief".

The justice of this arrangement, according to the Commissioners, was based on the fact that the food was given not as the price of labour, but as the relief of destitution. The labour given in return was the condition of receiving that relief; and if the necessities of the recipient and his family were wholly relieved, it was just that he should give in return the full value of his labour, whatever that was.

Temporary Extensions to Workhouses

A very large extension of workhouse room, partly of a permanent and partly of a temporary nature was brought into use in County Galway during the season of distress, 1847-52. As the enlargement of workhouse accommodation was at once too slow and too extensive a process, where only a temporary emergency had to be provided against, it was not much resorted to; and generally speaking additional room was obtained either by the erection of timber sheds on the workhouse grounds, or, more commonly, by hiring unused stores and other buildings as auxiliary workhouses. In many cases the buildings rented were not adapted to the purpose, and they were frequently so overcrowded at times as to prove absolutely injurious to the health of the inmates.