The Horror of Aughrim

Connacht Tribune Friday, July 12, 1991

The battle, like the dead, has long ago surrendered itself to the earth. You dutifully walk the battlefield and village in the hope of somehow conjuring up the sounds, the images, the sense of horror, of slaughter on such a massive and wasteful scale.

But the span of three full centuries has all but sealed the landscape. You pick your way along the well—trodden, well—dunged, cow path that leads up to the top of the tree—lined knoll at Urraghry. From his high vantage point you get a general's view of the two miles or so of land, across the breadth of which both armies clashed.

You see the gentle curve of Kilcommadan Hill on the horizon, the lush greenery of the landscape, the plentiful copses of trees, the parcelled—in fields, the barely perceptible spire of a church in the distance that signals the village of Aughrim, half—slumbering in the close heat of a hot July afternoon. But try as you will, you can't picture the scene.

High Cross near Aughrim village which commemorates the French General St. Ruth and all the soldiers who died during the battle.

Three hundred years later you can hardly imagine a tractor, let alone two armies of 20,000 men each, traversing this small plain beneath Kilcommadan Hill. Evolving agricultural practices has meant that the massive bog that filled out this valley and skirted the hill has been drained of its wetness, and reclaimed into a couple of dozen holdings which have changed the lie of the land perceptibly.

But pass over this plain they did, and engaged in carnage of a blood—curdling scale, never before or since seen on Irish soil. When the battle had subsided anything between 4,000 and 7,000 men had died with many many more injured, with the naked white bodies of the Irish dead "scattered like sheep" along the slopes of Kilcommadan Hill.

Nowadays, there are only faint reminders a sharp dip in the road that leads to Kilcommadan signals the spot where some of the most ferocious and barbaric of the fighting took place, and which has lived on in the memory as 'Bloody Hollow' the threaded remains of an esker a mile south of the village is a reminder of another bloody skirmish for Urraghry Pass, the occasional musket ball, coin, coil, dug up or uncovered by chance, the lone St. Ruth's bush in an open field which reputedly marks the spot where Charles Chalmont, the Marquis de St. Ruth, and leader of the Irish forces fell from his horse after his head was blown off by a stray cannonball, the sad ivy—strangled remains of Aughrim Castle (even then in ruins) rises from the ground like a rotten stump of a tooth, it was here that the battle was won for the Williamite forces and lost for the French—Irish Jacobite forces.

For the Irish, on the retreat since their failure at the Boyne a year to the day beforehand, it was a watershed battle, and a defeat that had greater consequences than the Battles of Kinsale, the Boyne, and Limerick. It resulted in a rout of such finality and ignominy that the Jacobite Irish Catholic army was decisively defeated and scattered, and also copperfastened the grip of William of Orange, and the planters of the North East, on the country.

But the battle had a wider significance than that, as it constituted an important stage of a wider struggle for power that was taking place at that time. It put paid to the expansionists aspirations of the French — who effectively commanded the Irish army — in regard to taking control of Ireland and Britain, while at the same time confirmed the rule of the Dutch House of Orange — whose forces included French Huguenots, Scots, English, Ulster Scots, Belgian, and Dutch — over the British Isles.

It was perhaps the greatest of the wars that took place on Irish soil at the time, but ironically, and sadly, the one that is least remembered. While the repetitive boom of the Lambeg Drums — "remember 1690" — and various year—long 300 "celebrations" (not much to celebrate, you would have thought) have reminded us about the events that took place on other fields.

But Aughrim is only a small place, by—passed now by the main Galway—Dublin road, with a population that only touches on two hundred. Until now, a sign on the road, and a solitary high cross surrounded by rusty railings in the middle of a lonely field have been the only memorials to the event. Even the cross is lucky to be there. It was originally constructed for the bicentenary of the battle one hundred years ago, but was left lying in Ballinasloe for many years because of a lack of funds to erect it. Through the efforts of local people it was finally put in place in 1960. In 1977 An Taisce put the railings around the cross to prevent cows scratching up against it. You feel that few climb over the gate, thread their way through the thistles and the high grass to read the inscription in three languages in memoriam of St. Ruth and all those who fell.

Aughrim is a small place, but the people of both denominations (there is a sizeable Church of Ireland congregation in the village), have worked tirelessly to ensure that the battle would be commemorated in a fitting manner. None worked harder — or gave of themselves more tirelessly — than the late Martin Joyce, the former headmaster of the local national school, who was an authority on the history of the battle, and whose lifelong dedication and enthusiasm ensured that it would not be forgotten. It was he who was the driving force behind the Aughrim Heritage Centre — under construction at present — which will undoubtedly help accord the battle its proper place in the public mind. Many of the models and artefacts in the heritage centre will have come from Martin Joyce's schoolhouse, which he had over the years turned into a veritable museum to the battle (and also to local heritage). Ironically, his death earlier this year came just as plans for the commemoration were reaching completion.

Schoolteacher Mrs. Jo Scannell, the Secretary of the Aughrim Heritage Society on Kilcommadan Hill. Part of the battlefield can be seen in the background.

Jo Scannell is an enthusiast, and why wouldn't she be, she says. She was born in Aughrim, and has lived there all her life. Martin Joyce was her teacher in school, and when she qualified from training college she herself came back to teach there. It was from Martin Joyce that she first learned of the battle that would be always associated with her village and through him, she and countless others learned to appreciate the magnitude of the encounter, and the deep deep implications it would have.

"He was always very enthusiastic about it," says Jo Scannell, now herself the principal at the national school, "and I suppose that enthusiasm rubbed off." Today, she and Meta Joyce, the widow of Martin Joyce, show us around the various points in the surrounding countryside that mark out the battle, and Jo Scannell takes us up to the top of Urraghry Hill to view the scene of the battle.

There was mist that morning that didn't rise until noon. St. Ruth, who had arrived in Ireland only two months beforehand, had failed to stop Athlone from falling to Williamite hands and had retreated his troops past Ballinasloe. Despite a disagreement with his senior Irish officers — including Patrick Sarsfield with whom he apparently had a personality clash — who said he should retreat to Limerick, St. Ruth decided he would make a stand.

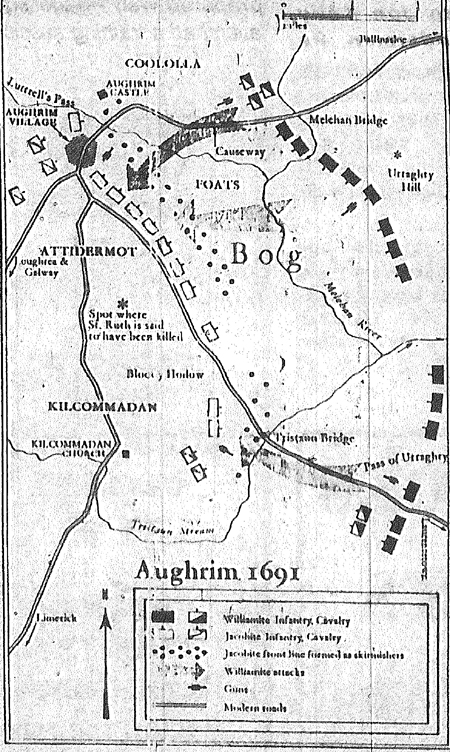

He chose the land around Aughrim and Kilcommadan Hill, which military historians agreed was an inspired choice. In front of the hill there was a huge morass of bog, through which it was almost impossible to cross. On the right and left of the hill, there were two narrow passes, the pass of Urraghry, and the pass at Aughrim Castle, which was so narrow that only two horses at a time could pass. For the Williamite forces to breach the defence, they would have to go through the bog, or force either one or the other of the two narrow passes. St. Ruth aligned his troops in the classic formation, cavalry and artillery on the passes at each side, with a large number of infantry guarding Kilcommadan Hill in the middle.

The Williamite forces that day slowly advanced eastwards from Ballinasloe, and knew they were facing the army when they encountered a few Jacobite outposts. Their leader was the Dutch soldier, Baron Godart de Ginkel, who was an experienced and highly accomplished soldier. Like St. Ruth's forces they too formed, with cavalry and infantry on the extremities with infantry in the middle.

At noon the fog rose like a curtain to uncover the scene of the two armies facing each other. Ginkel attacked at about 5 p.m. from all three fronts but was patently unable to penetrate the Jacobite forces who stoutly defended their positions. Indeed, to cross the bog, Williamite infantry had to wade chest deep in water only to be chased back into the bog by approaching cavalry once they hit dry land.

Saint Ruth thought that his right flank was vulnerable, but despite the bloody skirmishes that took place in Bloody Hollow, his forces held good.

As the evening progressed it began to appear as if the Jacobite forces would emerge victorious. They had resisted the fiercest of the enemy's attacks, and had maintained their fighting strength. However, Saint Ruth who rode to and fro along the mile or so of the battle—front throughout the conflict, decided that he would take some cavalry from the left flank to the centre, where he thought a breach might be made.

A senior English commander in the Williamite forces, Lord Hugh Mackay, spotted this and quickly deployed forces to attack the left of the Irish defences. But to no avail. St. Ruth, seeing Mackay's failure, remarked that his cavalry "were brave fellows, 'tis a pity they should be so exposed." Obviously confident of victory, he further proclaimed to his troops: "They are beaten — let us beat them back to the gates of Dublin".

On the move again, St. Ruth remarked in French "Le Jour est a nous, mes enfants." They were to be his last words, as what is thought to be a stray cannonball severed his head with the force of its impact. Confusion reigned amongst the Irish, and one of the Generals defending Aughrim Castle, Luttrell, is reputed to have taken to his heels and deserted the scene. With the French Huguenot cavalry closing in on the castle, those who defended it are said to have run out of ammunition for their cannon pieces, and were forced to use their buttons to ward off the enemy.

The position could not be held and the Castle was over—run. Williamite forces swept through the pass and wheeled around on the Irish infantry on Kilcommadan Hill in the centre, taking them by surprise. The carnage that followed was of awesome proportions. Historians reckon that anything between 4,000 and 7,000 Jacobite soldiers were slaughtered as the Irish were completely over—run. A contemporary testimony describes the blood of the battles as having "so inundated the fields that you could hardly take a step without slipping".

The defeat was final. The Irish survivors dispersed and straggled, with the cities of Galway and Sligo quickly falling to Williamite forces. The bodies of the Irish were left unburied on the battlefield, and apparently devoured by dogs and wolves, then still in existence in Ireland. The most famous ballad from the battle, 'The Dog of Aughrim, arose from the story of a wolfhound that apparently remained by the side of his fallen master for many months after the battle, and was finally shot by an English soldier.

In recent years, the poet Richard Murphy, has re—interpreted the significance of the battle, of the defeat, and of the problems of identity (he had people on both sides) in his brilliant epic poem, the battle of Aughrim. It is fitting that he will give a reading of the poem during the tercentenary festival, which takes place in the village this weekend. As the late Martin Joyce was wont to say it should be a commemoration, not a celebration.

Who owns the land where musket—balls are buried

In blackthorn roots on the esker, the drained bogs

Where sheep browse, and creedal war miscarried?

Names in the rival churches are written on plaques.

And a rook tied by the leg to scare flocks of birds

Croaks as I dismount at the death—cairn of St Ruth;

Le Jour est a nous, mes enfants, his last words:

A cannonball beheaded him, and sowed a myth

from Part 1 of the Battle of Aughrim, by Richard Murphy.