Robert O'Hara Burke

ByBackground

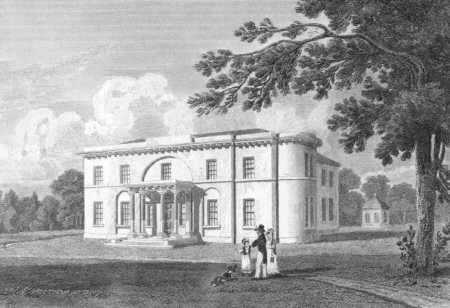

The exploration of central and western Australia has called forth many thrilling feats of endurance and courage, and resulted in some terrible tragedies, the greatest of which was that of Burke's expedition. Robert O' Hara Burke was born at St. Cleran's. The St. Cleran's property contained the Castle and lands of Mannin, a De Burgh residence in the Barony of Dunkellin, the north-western district of the diocese of Kilmacduagh, and situated within the present parish of Ardrahan. The castle is now but a square keep and partially ruined. It may be seen from the Indentures of Composition that Mannin Castle, at the close of the sixteenth century, was in the possession of Shane Oge Burke. The Burkes of St. Cleran's, direct descendants, held the lands of both Mannin and St. Cleran's until some years ago when they passed, by marriage settlement, to the Maxwells.

Robert O'Hara Burke was a son of James Hardiman Burke of St. Cleran's and of Anne, daughter of Robert O'Hara of Raheen, Co. Galway. His father took the name of Hardiman, in addition to that of Burke, in accordance with the will of his maternal uncle, Robert Hardiman of Loughrea, whose estates and property he inherited on his uncle's death in 1800. O'Hara Burke was educated in Belgium and at the age of twenty entered the Austrian army, in which he attained the rank of captain. Leaving the Austrian service in 1848 he joined the Royal Irish Constabulary, in which he served until 1853. In that year he immigrated to Tasmania and shortly afterwards crossed to Melbourne, where he became an inspector of police. During the Crimean War he returned to England and applied for a commission in the army, but before his case was fully considered peace was signed, and he returned to Victoria and resumed his police duties.

At the end of 1857 the Philosophical Institute of Victoria took up the question of the exploration of the interior of the Australian continent, and appointed a committee to inquire into and report upon the subject. In September 1858, when it became known that John McDouall Stuart, had succeeded in penetrating as far as the centre of Australia, the sum of 1,000 was anonymously offered for the promotion of an expedition to cross the continent from south to north, on condition that a further sum of 2,000 should be subscribed within twelve months. The amount having been raised within the time specified the Parliament of Victoria supplemented the fund by a vote of 6,200 and an expedition was organised under the leadership of Burke, with W. J. Wills as surveyor and astronomical observer.

Influence of John Mc Douall Stuart

The local researchers and the more comprehensive attempts of explorers to solve the chief problems of Australian geography, must yield in importance to the great achievement of John McDouall Stuart, whose efforts influenced the colonists and legislature of Victoria to finance Burke's expedition.

The first of Stuart's tours independently performed, in 1858 and 1859, were around the South Australian lakes, namely Lake Torrens, Lake Eyre and Lake Gairdner. A reward of 10,000 having been offered by the legislature of South Australia to the first man who should traverse the whole continent from south to north, starting from the city of Adelaide, Stuart resolved to make the attempt. He started in March, 1860, passing Lake Torrens and Lake Eyre, beyond which he found a pleasant, fertile country till he crossed the Macdonnell range of mountains, just under the line of the Tropic of Capricorn. On the 23rd of April he reached a mountain which is the most central marked point of the Australian continent, and has been named Central Mount Stuart. Stuart did not finish his work on this occasion, owing to indisposition and other causes, but he had reached the watershed dividing the rivers of the Gulf of Carpentaria from the Victorian river flowing towards the northwest coast. He had also proved that the interior of Australia was not a stony desert. On the first day of the next year, 1861, Stuart again started for a second attempt to cross the continent. This effort occupied him eight months, and he failed to advance farther than one geographical degree north of the point reached by him in 1860, owing to the barrier of dense scrub and lack of water.

Burke's Expedition

The story of Burke's expedition, which left Melbourne on the 21st August, 1860, is perhaps the most painful episode in the history of exploration. Ten Europeans and three Sepoys accompanied the expedition, which was soon torn by internal dissensions. Near Menindie on the Darling, Landells, Burke's second in command, became insubordinate and resigned, and the party's German doctor followed his example. On the 11th November Burke, with Wills and five assistants, fifteen horses and sixteen camels, reached Cooper's Creek in Queensland, 800 miles north, then far beyond the bounds of civilisation, where a depot was formed near good grass and abundance of water. Here Burke proposed waiting the arrival of his third officer, Wright, whom he had sent back from Torowoto to Menindie to bring some camels and supplies. Wright, however, delayed his departure until the 26th of January, 1861.

Meantime, weary of waiting, Burke with Wills, King and Gray as companions, determined on the 16th December to push on across the continent, leaving an assistant named Brahe to take care of the depot until Wright's arrival. As the party progressed they found that the savage sun had licked up all the water-holes before them and behind. There was practically no shelter. Their hair withered, their nails became brittle and cracked. The handles of the knives split; lead fell out of pencils; scurvy came on them. They had occasionally to fight off native attacks; horses and camels died, and they struggled through weeks of stone and sand desert under the blistering sun. On the 4th of February 1861, Burke and his party, worn down by famine and fatigue, reached the estuary of the Flinders river, not far from the present site of Normantown on the Gulf of Carpentaria, about 750 miles from Cooper's Creek.

On the 26th of February they began their journey home. The party suffered greatly from famine and exposure, and but for the rainy season, thirst would have speedily ended their miseries. In vain they looked for the relief which Wright was to bring them. On the 16th of April Gray died, and the emaciated survivors halted a day to bury his body. That day's delay as it turned out, cost Burke and Wills their lives; they arrived at Cooper's Creek to find the depot deserted. But a few hours before Brahe, unrelieved by Wright, and thinking that Burke had died or changed his plans, had left for the Darling. When provisions had entirely run out, they lived on the bounty of the natives who supplied them with fish and the seeds of a plant called nardoo - a diet sufficient for the aborigines but inadequate for Europeans. They took every precaution to preserve their journals. Wills died on the 30th June having kept up the entries in his diary until two days previously. Burke survived until the next day, the 1st of July, 1861. King sought the natives, who cared for him until his relief by a search party under Howitt on the 15th of September. Howitt buried the remains of Burke and Wills where they perished.

The report of the Royal Commission expedition was a virtual censure upon Burke's judgement in its conduct. No one can deny the heroism of the men whose lives were sacrificed in this ill starred expedition. The leaders were not bushmen and had no experience in exploration. Disunion and disobedience to orders, from the highest to the lowest, brought about the worst results. All that now remains to tell the story of the failure of this vast undertaking is a monument to the memory of the foolhardy heroes, from the chisel of Charles Summers, erected on a prominent site in Melbourne.

References: Robert O Hara Burke and the Australian Exploring Expedition of 1860. Andrew Jackson. London 1862.

.