John De Burgh, Archbishop of Tuam

ByJohn de Burgh was a descendant of a junior branch of the house of De Burgh and was born near Clontuskert in 1590. With his younger brother Hugh he received the rudiments of his education from a distinguished teacher named O' Mullally who resided with the De Burgh family until his pupils had acquired quite a considerable knowledge of Greek and Latin. The two brothers left for the continent in 1614, Hugh to Louvain, where he joined the Franciscans in St. Anthony's and John to Lisbon where he was entered in the secular college.

At the age of twenty-four John was ordained priest, and returned to Ireland about 1624, to the diocese, under Boetius Egan, where he worked for two years. On the recommendation of the bishop he was in 1627 appointed Apostolic Vicar of Clonfert. De Burgh's appointment took place during the deputyship of Lord Falkland whose persecution of the Catholics was intense. On the accession of Lord Strafford his anxiety for the proprietors of the province involved him in great difficulties, as he made himself decidedly obnoxious to the Viceroy by opposing, as far as he could, the projected confiscation of Connacht to the Crown. When the Parliament of 1634 was summoned he exerted all his influence with the Catholic members urging them to resist the scheme of spoliation under the pretext of inquiring into defective titles. This so enraged Strafford that he issued warrants for De Burgh's arrest. He remained in hiding until the Viceroy's recall. On the recommendation of his earlier patron, the Bishop of Elphin, he was appointed to the vacant see of Clonfert on 16th October,1641.

A large congregation among them Ulick, fifth Earl of Clanricarde, witnessed De Burgh's consecration in the Abbey of Kinalehan on 19th May1642. Malachy O'Queeley, Archbishop of Tuam, assisted by Egan, Bishop of Elphin, and O' Molloney, Bishop of Killaloe, performed the ceremony.

In obedience to the summons of the Irish Primate presiding at the general assembly of bishops and priests at Kilkenny, in the month of his consecration, De Burgh subscribed the ordinances agreed upon for persecuting war against the Parliament. From that time he resided almost constantly in Kilkenny where he assisted David Rothe, then in his seventy-second year, and in some respects unable to carry out Episcopal duties. De Burgh represented him at all the functions solemnised in the cathedral where he was engaged confirming and ordaining. Towards the close of 1643, the Bishop of Clonfert was elected a spiritual peer of the Supreme Council of the Confederates, which appointed him Chancellor. About the same time his brother Hugh was made the Council's agent and representative at the court of the Netherlands.

Notwithstanding the duties he had to discharge in Kilkenny, De Burgh looked to the administration of his own diocese. He reformed many abuses inseparable from the state of the times. He had many of the churches repaired and supplied with the necessary requirements, presided at synods of his clergy, and established schools. He favoured the policy of Ormond, as against what were termed 'extreme measures', at the Confederation, being influenced by his kinsman Lord Clanricarde who maintained strict neutrality during the early progress of the Confederates.

De Burgh had been three years Bishop of Clonfert when the archbishopric of Tuam fell vacant by the death of O' Queely. Without consulting the Primate or any other metropolitan, the Supreme Council recommended him as successor to the dead archbishop. The Papal Nuncio, Runuccini, who was then in Kilkenny, while deprecating the right of the supreme council to interfere in such matters - ancient privileges claimed by the English Crown - wrote to Rome a qualified recommendation of De Burgh whom he described as a man "of honest views, slow in speech, and suffering from an attack in the eyes, which might ultimately damage his sight." In the same letter he bore ample testimony to the fitness of Hugh De Burgh, whom he had met in Paris, stating that "he was a man of greater energy and activity, whose nomination was simply meant to reflect honour on the already consecrated."

Between the contemplated translation to the see of Tuam and the rejection of Lord Ormond's peace by the synod of Waterford in 1646, it would seem that the Nuncio had no greater friend or more active helper than the Bishop of Clonfert. In fact, of all the bishops and archbishops who declared against the Viceroy's overturns, none denounced them more than De Burgh. At that time Tuam was still vacant and the Nuncio was more anxious for De Burgh's translation. He urged the Vatican to lose no time in sanctioning it. About the time of the Waterford synod he wrote to Rome:

"That he had nothing more to say concerning the Church of Tuam save that six month's experience of the Bishop of Clonfert had convinced him that he deserved promotion."

Early in April, 1646, De Burgh was translated to the Archbishopric of Tuam.

On his induction De Burgh's first care was to restore the ancient Cathedral of St. Mary, which had suffered great dilapidation while occupied by Protestants and of which the architectural symmetry of its beautiful exterior had been destroyed. He re-erected the altars, replaced the furniture, and rebuilt the palace from the foundations. On the gospel side of the high altar of the Cathedral stood the sacellum or oratory in which the relics of St. Jarlath were kept, but which during the Anglican occupation had been unroofed and stripped. The relics, however, had been preserved in Catholic custody, and they were deposited in the restored resting place.

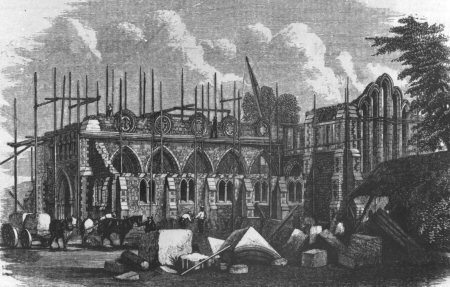

An 1865 photograph of the restoration of Tuam cathedral. This restoration took place almost 220 years after the restoration carried out by De Burgh. This photograph is available from the National Library of Ireland.

De Burgh's hospitality was unbounded as was his taste for books of which he made a great collection with a view of founding an extensive library in Tuam. A great admirer of the Jesuits he advanced them a large sum for maintaining their seminary in Galway, and in which town he built for himself a stately residence three storeys high.

Clonfert being now vacant De Burgh was anxious to have it conferred on his brother Hugh in preference to Walter Lynch, Vicar-capitulary of Tuam.Lynch, however, was strongly recommended by the Nuncio who had heartily come to dislike both De Burghs describing them as

"hot headed and wishing to have everything their own way ... that it would be unwise to have two brothers collated to the two best dioceses in the province ... that the Archbishop of Tuam was the most unmanageable and refractory of all the Irish prelates with whom he had to deal. He blames me for recommending Lynch and what is worse, he blames another who is superior to us all."

From this trouble over Hugh De Burgh began that mutual antipathy which influenced the Nuncio and the Archbishop in their future relations. A crisis was now approaching when the two were to met face to face in the Council of Confederates. During the whole of the year 1647 the Confederate armies were defeated in battle after battle. There was a great scarcity of money throughout the country; agriculture was neglected and famine and disease was rampant. The Nuncio was aware of this but he counted on money and munitions from abroad, and on the support of O' Neill's army, which was wholeheartedly behind him, and which he thought would sooner or later retrieve all losses and put him and the clergy in the ascendant. The Supreme Council on the other hand, could see no other solution than to make peace with Inchiquin and bring him over to their side.

A meeting called at Kilkenny resolved that French, Bishop of Ferns, and Nicholas Plunkett should travel to Rome and appeal to Innocent X to expedite the supplies which the Nuncio had already promised in his name. In the meantime the spiritual and temporal peers, together with the representatives of the Lower House had been summoned to Kilkenny on 23rd April, 1648, to consider the measures already taken to forward the end of hostilities, and to effect if possibly a union of Inchiquin's army with that of the Confederates so that both might act jointly against the Parliamentarians. Before the assembly fourteen of the bishops met in the Nuncio's house, and having examined the proposed treaty, a large majority declared:

"as it gave no certain guarantee for the free and open exercise of the Catholic religion and total abolition of all penal enactments against Catholics, they could not in conscience subscribe it."

Among those who condemned the cessation was the Archbishop of Tuam. His action astonished the Nuncio as he had already signed the instructions given by he Supreme Council to the Commissioners whom they had empowered to treat with Inchiquin. Inconsistent as it may appear De Burgh afterwards subscribed the articles of the cessation, and followed the policy of the party opposed to the Nuncio. He justified himself in a public statement: "that he never repudiated the agreement with Inchiquin but only certain clauses of it, which were subsequently altered and amended." The greater number of the bishops followed the Nuncio, and of the eight who opposed him the most formidable was the Archbishop of Tuam, whose influence was much appreciated by the party of Lord Ormond.

Apprehensive of his personal safety the Nuncio left Kilkenny, soon after the cessation had been concluded, and joined Owen O' Neill's army at Maryborough. He used every means possible to crush the Ormondists and prevent the Catholics from joining Inchiquin and Preston, who both hated O' Neill and the Nuncio. Sentence of excommunication and interdict against all abettors of the truce with Inchiquin, and the members of the Supreme Council were issued by the Nuncio. The opening of churches was forbidden as well as the celebration of Mass in all cities. All bishops and priests were commanded to proclaim this ordinance throughout the country, and chaplains of regiments specially ordered to read it aloud in camps.

The Supreme Council argued that the Nuncio had not jurisdiction, and appealed to Rome that the interdict must necessarily be null and of no effect. The minority of the bishops including De Burgh, with two of his suffrages, considered the sentence as uneconomical and unjustifiable. Nowhere were the censures so faithfully observed as in Galway, where the Nuncio lived before leaving the country. In Galway, however, the Archbishop of Tuam, with one of his suffragan and two friars of the Discalced Carmelites, preached openly against the Nuncio's authority and interdict. They were opposed by the Mayor, Warden and people. The Archbishop continued his resistance, had the doors of the Collegiate Church of St. Nicholas forced open and there officiated publicly despite all remonstrances. Another charge made against him to Rome by the Nuncio was that he had celebrated in the church of the Carmelites in Galway, who refused to observe the censures and were under excommunication in a full congregation of eight bishops and thirty theologians assembled within the walls of the town. Hoping to resolve the problem, the Nuncio convened a synod in Galway, but Clanricarde and Inchiquin acting for the Supreme Council intercepted the bishops on the way, laid siege to the town, which after surrendering, was compelled to pay a large indemnity.

Divided as it was between the two factions, one maintaining the Nuncio's censures, and the other insisting on the 'cessation' with Inchiquin the state of the country was appalling. French, Bishop of Ferns, says:

"Altar was arrayed against altar, the clergy inveighing against each other, and the bishops and best theologians in the land maintaining different views of the validity of the censures. As for the populace, they hardly knew what side to take, or what guide to follow, for in one church they heard the advocates of the censures proclaim, 'Christ is here,' and in another, 'He is not there,' but here with us who stand by the dissentient bishops and the appeal to Rome against the Nuncio's conduct."

Early in February 1648, as the Nuncio was awaiting a ship in Galway Bay to take him home from a country, to use his own expression, where "the sun is hardly ever seen," Ormond returned to Ireland as Viceroy. The Archbishop of Tuam and the Bishop of Ferns met him at Carrick and on their invitation he took over government at Kilkenny. Ormond had De Burgh and French duly sworn as members of his Council on the distinct understanding that they were to subscribe themselves under their surnames and not under their titles. This was an undignified compromise as on this occasion Ormond guaranteed the open exercise of the Catholic religion, possession of the churches with their revenues, and other advantages in the event of the success of the Catholic forces.

The Irish bishops, found, however, that Ormond was not to be trusted, and they met at Jamestown, at the beginning of August, 1650, and decreed that they would reconstruct the old Confederacy and hold themselves independent of the Viceroy whom they now regarded as an enemy of themselves and of their religion. The declaration was signed by fifteen bishops including the Archbishop of Tuam. Six commissioners were elected to treat with the Duke of Lorraine and invite him to land troops in Ireland then almost entirely in the hands of Cromwellians. In November of the same year the bishops adjourned to Loughrea where they pledged their loyalty to the King, and petitioned Lord Ormond to transfer the Viceroyalty to a Catholic. The Archbishop signed this document, and towards the close of 1650 he had the satisfaction of seeing Ulick De Burgh,, Earl of Clanricarde, his kinsman, installed in place of Ormond as Viceroy.

The negotiations with Lorraine came to nothing due to the imprudence of the Irish agents headed by the Bishop of Ferns, or to Clanricarde's dislike of the idea of foreign troops in Ireland. Sir Charles Coote, however put an end to the whole scheme by marching on Galway into which he drove Clanricarde's outposts on 12th August, 1651, and then encamped within a few hundred yards of the walls. During the siege the bishops from every part of Ireland took refuge in the town and among them the Archbishop of Tuam. Galway surrendered on 12th April, 1652, and the Archbishop made his escape to Ballymote near which he remained until 1654 when he was arrested and brought back under escort to Galway. Here he was robbed of his ring and other valuables and imprisoned with the clergy and the chief nobility of the country. He was detained there until August of the following year, and with many others he was put aboard ship and landed on the coast of Normandy. He then made his way to Nantes where he lived for five years, maintained by the French committee formed for the relief of distressed and expatriated Irish.

From Nantes he removed to St. Malo - a port then much frequented by Irish merchants - and within a year there left for Ireland reaching Dublin after a voyage of fourteen days, saying to Walsh, the Franciscan who rated him for returning without permission, "that he had come back to Ireland to lie down at rest in his grave and native soil." Ormond ordered the Archbishop to leave Dublin and owing to his infirmities he had to be carried in a litter, till he reached the neighbourhood of Tuam. Exhausted by illness and old age he seldom left his house. He had the Oratory of St. Jarlath situated on the right of the Cathedral, but detached from that building, re-roofed with tiles. He died on Holy Thursday, 4th April, 1667, and was buried in the Oratory of St. Jarlath. Eight days previous to his death by virtue of a special privilege he obtained from Rome, after having first sought and received ad cautelam, absolution for the Nuncio's censures.

Hardiman, in referring to the Nuncio, writes:

"In this dilemma he sought refuge in Galway, where he had some abettors, particularly the warden and others, whom his presence and exhortations stimulated to open acts of violence and commotion. The mayor was desirous to proclaim the cessation, but was prevented by the populace, who forced their way into his house, and wrested the ensigns of authority from his hands; but this insolence occasioned such a tumult, that, had they not been immediately restored by the very hand that took them, the consequences would have been lamentable; and, even as it was, two or three men were killed. The carmelite friars shewing some resistance against this proud ecclesiastic, their dwelling was assaulted by night and their persons abused. In a fit of rage he ordered their bell to be pulled down, and placed two priests at the entry to their chapel, to keep the people from resorting there for prayers. Those who favoured the cessation were declared under censure; the churches were closed, and all devine offices interdicted. In this state was the town, when the Archbishop of Tuam, who declared against these measures, arrived. Having desired to see the nuncio's power for assuming such authority, he refused to produce it, whereupon the prelate told him to his face that he would not obey: 'Ego,' answered the nuncio, 'non ostendam': 'et Ego,' replied the archbishop, 'non obediam,' and he immediately afterwards caused the church doors to be opened by force... The Nuncio who, thus finding his measures frustrated, took shipping at Galway, on the 23d of February following, and departed from the kingdom."

Sources

Prendergast. Cromwellian Settlement in Ireland.

Dunlop. Ireland Under the Commonwealth.

Bagwell. Ireland Under the Stuarts.

Commentarius Rinuccinianus.

Hardiman. History of Galway.

O' Flaherty. Iar-Connaught.

Meehan. The Rise and Fall of the Irish Franciscan Monasteries and Memoirs of the Irish Hierarchy in the Seventeenth Century.

Meehan. The Confederation of Kilkenny.

Lynch. The Life and Death of the Most Rev. Francis Kirwan, Bishop of Killala.